A look at the changing restaurant scene in Pihladelphia’s Chinatown

By Qingyi Gong

Philadelphia’s Chinatown is a popular dining area in the Center City. Search “Chinatown restaurants near Philadelphia, PA” on Yelp, more than 200 entries will appear, along with thousands of food reviews from Chinatown diners.

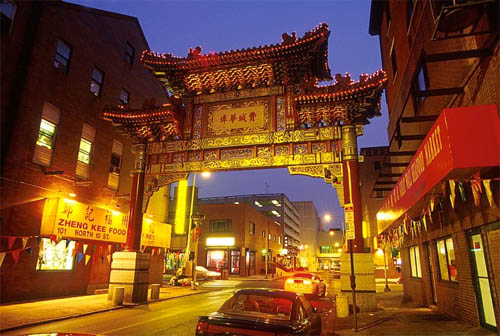

Philadelphia’s Chinatown is small. Its core area spans roughly from North 9th to North 11th Street and from Arch to Vine Street, with banks, barber shops, Asian supermarkets, clinics and a mix of other community facilities.

But it’s the food that accounts for most tourists’ enthusiasm. The small neighborhood lays claim to some of the nation’s best Chinese restaurants and is traditionally seen as a paradise for Cantonese and Hong Kong cuisines.

“Dining in Chinatown kind of reminds me of the Hong Kong movies I watched,” said Shuyu Meng, a freshman at Bryn Mawr College. “I once went to Joy Tsin Lau with my friends to drink early breakfast tea. I’d say the Cantonese food there was fairly authentic. The choices of dim sum were also not bad compared to what I ate in Hong Kong.”

Hailing from a northern province in China, Shuyu said she personally liked Hong Kong food. The only thing she complained about was that there were fewer choices of congee, a rice porridge, available in Chinatown.

The first Chinatown restaurants were opened by immigrants from the southern region of China. The legacy continues till today. A lot of restaurants, such as Siu Kee Duck House, Ting Wong Restaurant and David’s Mai Lai Wah, still use traditional Cantonese spellings on their signboards and sell mostly Cantonese style food.

However, a new trend has taken place in Chinatown in recent years, as many budding restaurant owners started to sell Sichuan, Shanghai, Lanzhou and other regional foods of China. While Taiwanese, Cantonese and Fujianese flavors are still dominant, Sichuan and northern China cuisines have become real hits in Chinatown.

Hong Kong Wonton Soup, Beef Chow Fun and Roast Pork Congee, which are common Cantonese dishes, have disappeared on the menus of some new restaurants. Instead, trendier eateries offer Shanghai Crabmeat and Pork Juicy Buns, Dan-dan Noodles and Ma La Hot Pot at acceptable prices.

The Shanghai Xiao Long Bao sold at the Dim Sum Garden has a wondrous taste. Topped with tiny spots of yellow crab powder, the eight flour-made buns form an exquisite circle in a bamboo container. Every bite is a delight, for the buns contain a lot of meat soup inside. And customers can drink soup while eating the yummy pork stuffed inside the buns. Another restaurant, Sakura Mandarin, just steps away from Dim Sum Garden, also sells authentic Shanghai food.

The boom of Chinese regional foods in Philadelphia’s Chinatown began more than a decade ago. Most notably, the number of Sichuan restaurants has increased significantly and Sichuan food has been in vogue in the neigborhood.

But the popularization of Sichuan food has been gradual. Most people in Philadelphia came to know Sichuan food through a restaurant called Han Dynasty, owned by Han Chiang.

“Almost everyone becomes familiar with Sichuan food through Han Dynasty. The restaurant opens a door for people to know about this type of food,” said Craig LaBan, restaurant critic and columnist of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

LaBan said the wide popularity and success of the Han Dynasty restaurant may have “created a ripple effect in the region of Chinatown”, inspiring people there to open their own Sichuan food restaurants.

Szechuan Tasty House and the Four Rivers are among the oldest Sichuan restaurants in Chinatown. But newer restaurants have also been opened over the past few years. E Mei Restaurant, located at 915 Arch Street, is one of the largest Sichuan restaurants in the area. It was opened three years ago and occupies the original site of a Chongqing restaurant.

Szechuan Tasty House and the Four Rivers are among the oldest Sichuan restaurants in Chinatown. But newer restaurants have also been opened over the past few years. E Mei Restaurant, located at 915 Arch Street, is one of the largest Sichuan restaurants in the area. It was opened three years ago and occupies the original site of a Chongqing restaurant.

The restaurant is jointly owned by two immigrant families. One of the owners comes from Sichuan Province.

E Mei sells classic types of Sichuan food. Famous appetizers on the menu include Sliced Chicken in Hot Sauce, Sliced Beef and Tripe with Chili Sauce, Sliced Pork with Garlic Soy Sauce and Hot and Spicy Shredded Pork. For entrees, the restaurant offers Dan-dan Noodles, Cold Noodles, dumplings and wontons, or Chaoshou in Sichuan dialect. Fried dishes like Ma Lai Fragrant Pot and Piao Xiang Tripe are also extremely popular. The restaurant’s menu is dotted with small red dried chili symbols, which denote “hot and spicy” for specific dishes.

The chief chef of the restaurant comes from Chongqing, according to the staff at E Mei Restaurant, according to Xuejian Yang, the manager. “The chef has previously worked in a five-star restaurant in China and makes sauces for the dishes by himself,” Xuejian said.

E Mei has a main lobby with 18 tables and one private room with two tables. It has hired four chefs, an appetizer preparer and several waiters. There are six to seven people in total on their staff list.

Business gets a lot busier on weekends. “Most customers come on Friday, Saturday or Sunday, and we close later on Friday and Saturday nights at 11 p.m.,” Xuejian said.

E Mei Restaurant has created several new dishes for the winter season, including a braised lamb stew dish, which is made from special soup stock. Xuejian especially recommended the hotpots in his restaurant, which have spicy flavors and are said to be popular among students and tourists.

E Mei has been successful in advertising the spicy Sichuan food in Chinatown. And many new restaurants followed its path. Tango, another restaurant on Arch Street, now has a chef from E Mei to cook the spicy Sichuan dishes for its customers.

Lan Zhou Noodles, a famous dish in the northwest region of China, has also found its way to Philadelphia’s Chinatown. There are at least two noodle houses open in the neighborhood, one on North 10th Street, the other on Race Street. Jenny Zhang, 36, works at the Nan Zhou Hand Drawn Noodle House on 1022 Race Street. She said the restaurant opened almost 11 years ago and sells mostly noodle dishes, which are very different from Cantonese food. Another noodle house, called the Yummy Lan Zhou Hand Drawn Noodle House opened in 2009, at a date much later than the first one but seems to be equally popular.

The Lan Zhou noodles sold in the North 10th Street restaurant are two types: Hand drawn and hand shaved. Try their House Special. The beef is tender and copious. And the soup tastes fresh. A thin layer of chili oil looks shiny on top of the dense and fragrant broth. “All noodle bowls come with spinach, Cilantro and scallion,” the menu states. The restaurant has been promoting a new product since October this year: the Firing Hot Noodle Soup. Just add an extra $1.25, and customers will get a bowl of extremely hot and spicy noodles.

“Many people like spicy food,” Mrs. Lin, the owner of the Lan Zhou Noodle House said. “I have seen many of my customers grab the chili oil bottles on the table and pour more chili into their noodle bowls,” said Lin.

However, not all the new restaurant ventures in Chinatown end up successful. A northeastern Chinese restaurant opened around 2010 is now closed due to the lack of customers, according to Xuejian.

The Chinese regional food boom in Philadelphia’s Chinatown is not an accidental phenomenon and the causes may be complex.

Demographic changes in Chinatown’s local population explain little about the new trend. A long-time reporter on Chinatown and Chinatown’s restaurants, LaBan said he did not believe there were any obvious changes in Chinatown’s demographics in the past few years.

But at least three factors have contributed to the new trend among Chinatown’s restaurants. According to LaBan, Philadelphia’s Chinatown has witnessed “a massive influx of Fujianese entrepreneurs over the last 5-to-8 years who’ve been far more eager to open restaurants with diverse regional flavors than the Cantonese old guards were ever willing to do. ”Most of them are “migrated from the New York market,” he said.

LaBan thinks the arrival of those restaurateurs may largely account for Chinatown’s recent regional food boom.

More chefs also come down from the New York City, bringing a variety of cooking techniques that are dramatically different from the Cantonese traditions in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. The chefs at the Yummy Lan Zhou Noodle House on North 10th Street all came from New York. They worked previously at restaurants in the Flushing district of New York City.

The chefs who have come from New York “kind of want to reflect a diversity of flavors they experienced in the restaurants in New York”, said LaBan.

By revolutionizing their dishes, many Chinatown restaurant owners also hope to attract more customers from the Greater Philadelphia area. An increasing population of Asian students in Philadelphia and the surrounding areas also contributes to the current boom of Chinese regional food. College students from China and other Asian countries form a solid customer base for Chinatown’s newly established restaurants. New restaurants are often trendier and more appealing to young customers who desire to dine in a more modern and comfortable environment.

Sakura Mandarin’s full menus of drinks, cozy chairs and good red tea make it more appealing than the often bare, plain and somewhat greasy interiors of the old Cantonese restaurants. Chinatown is also a short distance away from a number of universities in Philadelphia. And students from Temple University, Penn and Drexel are some of the frequent diners there. “Some of the restaurants offer KTV services. Many students come to eat there and then they can hold karaoke parties,” said Xuejian.

E-Ni, the owner of the Hunan Restaurant at 47 E Lancaster Avenue in Ardmore, said the spicy food from Sichuan and Hunan can suit the tastes of a variety of customers. “People change their eating habits when they travel around the world. And even those who are from southern provinces in China are beginning to accept spicy food like Sichuan dishes.”

Many restaurant owners are constantly improving the regional foods they sell to adapt to the American appetite, thus making those regional foods more popular in this area. One of the chefs at the Lan Zhou Noodle House said: “In the northwest China, people don’t use soy sauce to cook Lan Zhou noodles. But here in American, we use the soy sauce to improve the original flavor. The noodles look dark and shiny when scooped from the cauldron.”

“Our store is trying to create a flavor which suits the Chinese customers, northerners and southerners alike, and the many non-Asian tourists,” the owner of the Lan Zhou Noodle House said.

The influx of tourists from mainland China into Philadelphia’s Chinatown may also have driven the new trend. “We host tourist groups from mainland China almost every week. Sometimes the group has a dozen of people. Sometimes there will be only six or seven diners. And customers from China typically like to order spicy dishes like fried tripe, double sautéed pork and shredded pork in garlic sauce, etc.”

“There are more visitors from Sichuan and northern provinces of China in recent years,” Xuejian observed. “Last night, we hosted 10 tables of visitors from mainland China in the main lobby and four tables of tourists were from Sichuan Province. We have waitresses from Sichuan, and they knew the dialect those customers spoke at once.”

So far, the current regional food boom in Philadelphia’s Chinatown doesn’t seem to pose a threat on the older Cantonese and Fujianese restaurants. Cantonese restaurants are still popular among the locals and some tourists. A Guangdong immigrant, who has lived in Chinatown for about a decade, said old folks of Chinatown are not used to eating at the spicy restaurants. “The Cantonese people like to eat dishes with lighter flavors,” this man said. “It is hard to let them change their appetite.”

He and many locals often dine at the Ocean Harbor, a medium-sized Cantonese restaurant at 1023 Race Street.

Meanwhile, the old restaurant brands in Chinatown, such as Joy Tsin Lau, are still serving as essential gathering places for weddings, family reunions and other important occasions among the local community.