The journalist and author has spent a lifetime pursuing stories about people

By Colin Battis

“I stayed by the phone that entire time, just waiting to be sued. A week, maybe ten days later, I got a call from the main source, who was a medical examiner. He told me she had confessed, and nobody else knew. I remember I fell on the ground in my office crying, because I realized at that point how worried I was, ‘cause we hadn’t heard anything, that we had gotten some major thing wrong.”

Stephen Fried speaks casually about solving the largest-ever case involving children killed by their own mother, sitting in an office that seems like that of a stereotypical professor or academic. Every available surface of desk, shelf, or windowsill seems weighed down by books, magazines, or sticky notes.

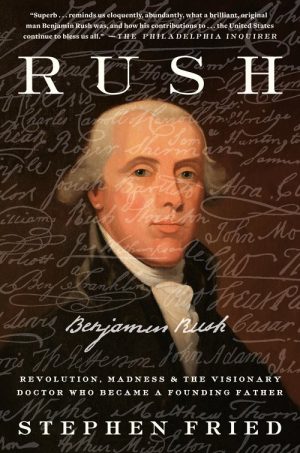

Some of that material relates to Fried’s latest project: a foray into history to write an acclaimed biography of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and important figure in treating mental illness.

As he leans back in his chair, Fried’s face is accidentally framed next to a bobblehead figure of himself, which does a great job of capturing his shock of curly white hair and the eyebrows that arch sternly above his glasses.

Author and Journalist Stephen Fried

There are a few concessions to the accomplishments of his 40-year career in journalism- framed newspaper articles and magazine covers, copies of his own books, and a cluster of awards. One of those awards is a medal from the Vidocq Society, an organization of forensic professionals specializing in cold cases, given to him for his investigation of a woman who had killed eight of her ten children and had gotten away with it, fooling authorities into believing it was a tragic case of SIDS.

This is the story Fried is currently caught up in telling, having passed the part where he turned over his material to the police and just now caught up to when the killer confessed to her crimes.

“People always said that this woman is either the most sympathetic woman in history and we were reopening every one of her wounds, 30 years later,” Fried said. “Or this is the worst unsolved crime in the history of being a mom, in which case you are saving the memories of the most kids ever killed by the person who gave birth to them…”

Though he might look perfectly suited to the stereotype of a ‘writer’, Fried is harder to pin down in person, leaning back in his office chair and seeming to enjoy each question that comes his way as an exercise in dissecting his own career. He pivots from decade to decade, jumping from high to low points as he questions or looks back fondly on his own decisions and strokes of luck.

To one side, a table of signed basketballs and other souvenirs hints at the game of half-court he and a group of friends have been playing three times a week for 27 years. Like everything else in his life, including marriage to novelist Diane Ayres and “playing the cool uncle” to his numerous nieces and nephews, the half-court tradition has at one time or another been fed into Fried’s passion. His writing.

“When you write for newspapers or magazines, you write so many stories you can’t even remember the ones people don’t still talk about… This is personal work, its hand work. There’s nothing machine made about it, and there’s a lot of different places where things could have been better or different.”

Fried isn’t being unnecessarily modest, it’s more that he’s matter-of-fact. When something touches every aspect of your life like writing does for the Philadelphia journalist, it becomes a natural extension of yourself. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Fried, who often refers to people as “characters” and who describes major events in his life in terms of what stories he was working on at the time, is driven to capture reality on the page.

“Mostly what I’m looking for are pieces that are long, character driven, and that feel like you’re watching a movie but it’s all in words,” Fried says. “I’m a very nosy person. I wanted to tell stories that looked at characters in all their depth.”

That interest in people is what led him early on to begin writing stories that examined mental illness, a journalistic focus that has been present throughout his career.

“It’s very clear that mental illness and addiction are so much a part of the landscape, and a part of it that people don’t know how to report on,” he said. “From the very beginning, all I was looking for was to be accurate to that.”

Fried encountered this reality with his first magazine story to gain major attention. “Over the Edge,” published in 1984, dove into the lives of five Bucks County teenagers, three of whom killed themselves over a short span of time.

Fried now speaks with a mixture of admiration and relief for his younger self when remembering his time investigating those events. During his reporting, he gained access to the tape two teenage boys had made of the hours leading up to their mutual suicide — though at 26, “I didn’t realize I’d basically been handed a holy grail… [That] story is always going to be the best thing I ever did, just because I was so young and so impossibly in over my head… and it still matters today. There aren’t that many stories that really go inside a set of suicides.”

With the reader response to the stories on mental health he continued to pursue, “I started viewing myself as a writer of cautionary tales about mental illness and addiction, tales that would engross readers but also have a really good reason for being retold,” Fried said.

Just last spring, he taught his own course at Penn on writing about mental health- a personal goal throughout the many years he has spent teaching journalism and mentoring graduate students at Columbia and Penn, an aspect of his career he has maintained for nearly 20 years, though he does play modest about it.

“I never wanted to be a full time teacher. I feel like I’m a decent teacher who comes from industry, and can offer certain kinds of teaching for certain kinds of people,” he said. ”I’m interested in trying to teach other people to do this journalism in a way that doesn’t overburden it, but takes it seriously.”

Colin Battis is a Haverford College student covering literary Philadelphia.