Three scientists struggle to reconcile science and belief in God

By Harper Hubbeling

“Fine. I quit,” said Judy Owen.

It was a brassy move. Graduate students don’t usually march into their advisors’ offices and threaten to resign.

But Owen was mad. Norman Kliman, Owen’s thesis advisor in the biology graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, had just threatened her belief system.

“He said he was deeply troubled by my being a churchgoer and – this is a direct quote – he said: ‘Your capacity to accept anything on faith is detrimental to your progress as a scientist,'” recalls Owen, in a heavy English accent.

“I told him that I felt my spiritual life was my guide,” she says, “it was my moral compass. It was a part of who I was and I could no more cleave that from myself than I could cut off a finger or an arm.”

As far as Owen was concerned, if Kliman felt she could not succeed as a spiritual scientist, she “needed to get out of science right then.”

But Kliman backed down. Owen did not quit.

Thirty-one years later, Owen, a professor and researcher of immunology at Haverford College, is still in science. And she is still spiritual.

Owen is not alone. According to a 2007 study from the University of Buffalo, 48% of U.S. scientists report a religious affiliation. Yes, this is less than the 76% of the general population that claims affiliation. But it still raises eyebrows.

Half of U.S. scientists don’t see a conflict between faith and science? Why not?

Kliman wasn’t just some crazy old spiteful professor. He’s hardly the first to suggest that science and the church might clash – the two don’t exactly have a history of getting along. Witness the long and continuing dispute among Creationists and scientists over when and how life began on earth.

But 48% of scientists have found a way to live in both worlds. Three Haverford scientists, Owen and her colleagues Jenni Punt and Fran Blase, are among those living with the tension between science and faith. Listening to their stories, how they’ve wrestled with being “believers” in science, we see that embracing both worlds is possible – but not always easy.

While they practice their faith to different extents, all three women scientists say they do suspect there is a higher power.

“I do believe there is something else out there,” Owen says.

What is that un-measurable something? Owen admits she doesn’t know. But she’s reluctant to let anyone else give her an answer.

“To take something which is so deep and so meaningful and let somebody else define it for you – there are real problems,” says Owen.

“The hardest thing for me to cope with is, ‘I am the way the truth and the light. There is no other way to the Father but through Me,'” she says, quoting Jesus in John 14:6.

Owen does not interpret the Bible literally, particularly not the Old Testament.

“In the Old Testament you can find evidence for anything,” Owen says.

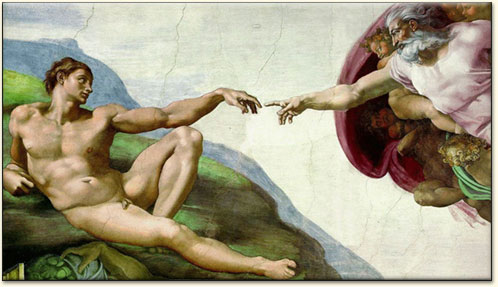

For Owen, the “day” that God created man, “could be from the dawn of time until however many thousands of years ago that man emerged.”

Owen applies the same interpretation and skepticism to what she hears from the pulpit as well.

“I’m more likely to resist an evangelical preacher who tells me this is what I must believe than I am to resist a fact in science,” she says.

It seems that Owen’s “capacity to accept anything on faith,” is not so developed as Kliman feared.

Owen wasn’t bluffing when she walked into Kliman’s office that day. She would’ve walked out of science for her spirituality in an instant.

But for Owen it goes both ways.

“When the church pulls dogma that runs counter to science then I leave the church dogma behind,” says Owen.

Jennie Punt

Owen is not the only believer willing to put science before the church.

“Evolution does come a little before religion for me,” says Jenni Punt, another Haverford professor and immunology researcher. Punt says she does see a conflict between certain religions and evolution.

“You have to face that squarely,” she says of the conflict, “it limits the kind of religion one can adopt.”

Punt was raised Protestant. She was brought up to believe in the good in all people – and to go to the best sermon. At age 12, Punt stopped going to church with her family. By 17, she had rejected God entirely. “I was a strident atheist for a while,” says Punt.

Turning away from God was a conscious, thoughtful decision for her. And it was a frightening one.

“I decided that God didn’t have to exist and that was really terrifying to me,” says Punt, “I had to relearn how to walk, frankly.”

Now 48, Punt has backed off from her radical atheist stance – somewhat.

“I don’t think there is a need for a God,” says Punt, “but I don’t think that necessitates the non-existence of God.”

Punt says her career as a scientist has impacted her religious views.

“In science I see so many possibilities of knowing,” she says, “I cannot just blindly say, ‘Oh, I don’t know that.'”

Punt tilts her head upward as she remembers her mother.

“My mother would say, ‘God is to us as we are to ants,'” Punt says slowly, “but unlike ants, we are still probing what we can know.”

Punt has made a career out of probing the boundaries of human knowledge. “Science allows me to see the things that we can know,” she says, “but it isn’t the only thing I see as a route to understanding what we know and what we don’t.”

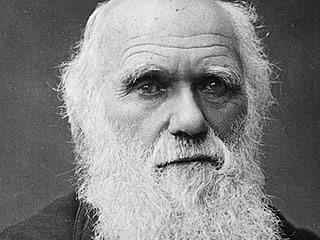

“I love Darwin so much, but there is a beauty to Darwin that I can’t attribute to Darwin,” Punt confesses.

What gives Darwin that inexplicable beauty?

Punt subconsciously wrinkles her nose when faced with the idea of a traditional single God figure. “It is not a conventional thing for me,” she says.

Over her life, Punt has toyed with quite a few unconventional possibilities. She’s intrigued by polytheism because she says it helps her explain why bad things happen to good people.

In college, Punt dreamed up an even less conventional outlook.

“I decided that God didn’t exist yet but we were creating him,” Punt says. She had decided any God she could believe in would have three attributes: omniscience, benevolence, and omnipresence.

Punt sees most religions falling short on omnipresence – serving only some people and ignoring, or even excluding, the rest.

“I have such a strong rejection of the notion of religion that excludes things,” says Punt, “I will never be part of a religion that says ‘I am this and you are not.'”

“I’m stridently against religion as a crutch and an ostracizer.” Punt adds.

Punt also says she hasn’t seen enough evidence of a God who is both good and powerful.

“If you are omnipotent, then I don’t see enough benevolence in the world,” Punt says,” addressing a potential higher power with frustration in her voice.

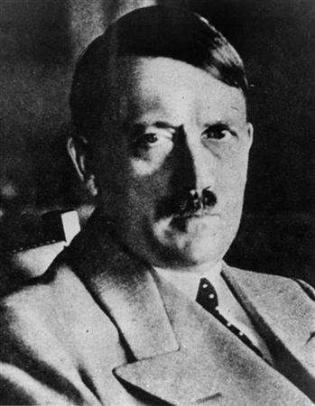

“The Holocaust, since I was little, never fit into anything I understood,” says Punt, “it doesn’t make sense to me.”

Like Owen, Punt would – and has – turned away from all religion that runs counter to science. Punt is also quick to turn away from religion that runs counter to that one fundamental belief engrained in her as a child: to believe in good.

If God made the Holocaust, or any holocaust, Punt wants nothing to do with him.

“If that is the kind of God that exists, I will fight against it till the day I am judged if that is what happens,” says Punt.

Fran Blase

“What would happen to Adolf Hitler?” asks Fran Blase, an organic chemistry professor at Haverford, sitting in her office in the chemistry wing, just two flights below Punt’s office.

Asked about God, Blase’s mind also went to the Holocaust.

“Did he have a soul?” Blase asks about Hitler, “and what happens when he dies? Is it really just over?”

Unlike Punt, Blase doesn’t blame God for creating Hitler, but she does look to God to punish him. “You would like to think that there is a place called hell for people who really do evil things,” Blase says.

Blase likes Purgatory – or rather, the concept of Purgatory. She laughs as she jokes that it is a selling point for the Roman Catholic Church.

Blase was raised Roman Catholic and is still practicing.

“I may be the only practicing Catholic on the faculty,” she says.

Unlike Punt and Owen who have abandoned organized religious services, Blase attends Mass every week. And she loves it. Blase describes Mass in a tone most would reserve for gushing about a beach vacation in Hawaii.

“I’ve got 45 minutes of peace,” she says, “all the nonsense of the day and the week and the busy life just sort of disappears. It’s my 45 minutes of solace, of listening to beautiful music, relaxing, thinking about the world and not about me, thinking about how maybe there is a God out there who is looking over all this.”

“It is really very fulfilling for me personally,” she says.

Religion, for Blase, is also about culture.

“It became ingrained as part of our fabric, of who we are, because so much of our lives revolved around traditions and ceremonies and holidays that were associated with our religion, with being catholic,” Blase says.

But Catholicism is more than a mindless childhood habit for Blase. And it’s more than just a weekly break from stress. Blase made an active decision to remain a practicing Catholic based on the church’s commitment to social justice.

She is proud of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s impressive dedication to charity. She’ll tell anyone who’ll listen about Sister Mary Scullion’s work with the homeless.

“The Catholic Church does an amazing amount of outreach and good,” says Blase. “It’s an amazing organization and I’m glad to be a part of it.”

Blase knows not everyone has such a glowing impression of the Catholic Church.

“People say, ‘How can you still be a member of the Catholic Church,'” Blasé recounts, “and yes, it’s got some major problems.”

Here Blase shares some of Punt and Owen’s capacity for skepticism.

“I don’t always agree,” Blase says of the Catholic Church’s social ideology, “I like to think that at times I’m a good force in the Catholic Church because I’m the voice of dissention,” Blase laughs.

But while Blase laughs at her self-proclaimed role as dissenter, her self-granted liberty to stand within but apart may be what makes religion compatible with science for her.

All three women have redefined what religion is asking of them, throwing out the pieces that conflict with their devotion to science. Owen’s religion doesn’t ask her to read the Bible literally. Punt’s religion doesn’t require her to see a conventional God.

And Blase? Blase’s religion doesn’t ask her for blind faith in anything.

“You do accept some things on faith, but you question a lot,” she says, “we often say that God has a plan, so I guess you can say you are accepting this plan on faith, but then you are also questioning: well, what is the plan? What do you think his intentions were? What good can come of this? Is there a God?”

Blase goes so far as to suggest that religion might even help her with science.

“I think religion is good training actually, for science, because you are always thinking and questioning,” she says.

Norman Kliman probably would not agree. He wasn’t worried about his graduate student attending church because he thought it was a workshop on questioning.

Kliman clearly saw a fundamental difference between science and religion – one open to questions, one blind to them.

Blase doesn’t make that distinction. She sees imagination in both.

“They are complex things that are difficult to visualize,” she says, “it’s all about imagining the unimagined.”