Isn’t bad at all for Annie Anderson, who works at Eastern State Penitentiary

By David Roza

The room looks like a set from a horror movie. Walls of fractured tile, chipped plaster and exposed brick surround a grimy floor and a ceiling of broken glass, sepia-toned with dust after decades of disuse. A surgery lamp the size of a car tire with four enormous light bulbs hangs precariously from a rusty fixture like a macabre chandelier in the middle of the gritty room. The chilly air blowing in from the October wind outside gives the room an eerie, spooky mood.

“So, this is where Al Capone got his tonsils taken out!” says the red-nosed, blonde-haired woman who lights up the gloomy room with her warm disposition and kind smile. Her name is Annie Anderson, and she is the Historic Site Researcher at Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia’s infamous prison-turned-museum where the notorious Chicago crime-boss Al Capone did indeed have his tonsils removed during his brief stay at Eastern State in 1929.

Like Capone, Anderson hails from Chicago. The young historian majored in English at Calvin College before working as a journalist for various publications and earning a Masters degree in American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston. Unlike Capone, Anderson hopes to stay at Eastern State for quite some time.

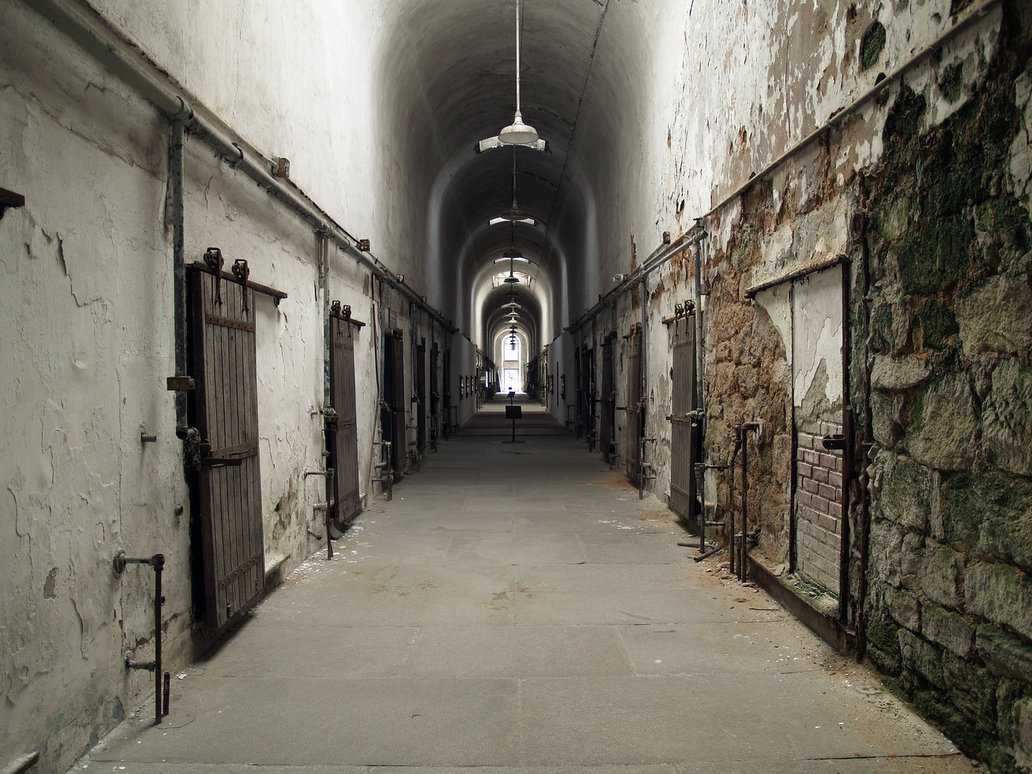

“It is really fun to be employed as a historian…it’s sometimes hard to imagine all of the people who  lived here because right now it’s so empty and quiet and abandoned,” says Anderson amidst the still sobriety of the tomb-like ruin. “I love that I can imagine it being populated by the inmates.”

lived here because right now it’s so empty and quiet and abandoned,” says Anderson amidst the still sobriety of the tomb-like ruin. “I love that I can imagine it being populated by the inmates.”

It is indeed difficult to picture that this half-dilapidated building—whose historical exhibits are interspersed with heaps of rubbish and piles of broken masonry—was once a bustling penitentiary that housed 1,700 inmates. The 184-year-old building was shut down in 1971 because its aging infrastructure could not support a rising inmate population.

The abandoned building quickly deteriorated into an overgrown urban forest that housed little more than a colony of stray cats. Efforts to restore the building for historic preservation began in the late 1980s, and the penitentiary was opened for tours in 1994. According to Eastern State’s website, easternstate.org, early visitors had to sign liability waivers and wear hard hats to avoid the risks of walking through a building that had nearly crumbled into collapse.

When asked about the wreckage, Anderson said, “Eastern State is trying to pursue this interesting way of being a stabilized ruin. We try to stabilize the spaces that are here without necessarily altering the landscape or doing massive improvement projects, so that the building looks like what it did when it closed in 1971.”

Anderson’s role as Historic Site Researcher is to uncover through archival research the details of the penitentiary’s living past, hidden somewhere beneath the debris.

“I really like the process of hearing and telling stories,” said Anderson. “We have some stories of inmates who gave birth at Eastern State and got to keep their babies at least for a little while before being sent away to family and friends who could care for the baby. Those facts make those people who were incarcerated very real to me.”

The building today is in a much better state of repair. Visitors no longer have to sign liability forms or wear hard-hats as they stroll through cleanly marked and polished exhibits. However, there are still corners of the vast complex that look like they were bombed 30 years ago and never repaired.

One of these corners was a former kitchen that sits along a series of counters and dining rooms that inmates once called ‘Soup Alley.’ Stacks of lumber and fallen drywall have piled up in the kitchen beneath a giant, crooked stove hood while pockets of grey, cloudy sky poke in through holes in the ceiling above.

Anderson’s clear voice resonates out from beneath her bright blue and green scarf and reverberates around the still, grey room as she explains, “Inmates went down this passageway to the serving counters where they got their trays and their food, and they went down either this door or that door to the respective cell block dining halls. We have some footage from a 1929 film of inmates herding around carts with fresh bread and things like that on them.”

At first, it’s hard to imagine anyone eating anything other than a nasty mouthful of sawdust and tetanus in this dump. But as Anderson’s narration continues, the rubbish clears away and one can picture the movement, the noise, the dishes and discussions of a group of human beings who lived and ate here long ago.

Anderson’s calm voice is offset by her eyes, which brighten up at the sight of their aged surroundings. She stops near the high stone walls as the chilly wind whips her hair around her forehead. The clouds have parted and revealed a fierce blue sky that matches Anderson’s eyes. The buildings of modern Philadelphia surround the ancient penitentiary, a microcosm of buried history restored to life by the loving efforts of people like this kind woman from Chicago. I ask Anderson what draws her back to Eastern State every day.

“I live in West Philly; biking to work down Fairmount Avenue and seeing this huge fortress, this incredible building which I get to work in…and that idea of telling these stories that haven’t been told yet is very inspiring to me.”