The Eiselen Bakery in Roxborough has been a family business for 100 years.

But can it remain in the family? A daughter explores the options

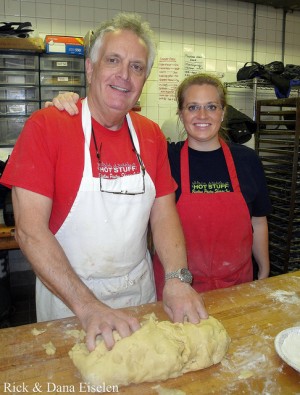

By Dana Eiselen

The door bell chimes as I walk into the bakery. Heat from the oven defrosts my cheeks of the bitter November air. It is 7:30 a.m., and the store is bustling.

A boy of three or four presses his nose and hands on a glass case, staring down a cupcake. The cases are filled with piping hot pies, cinnamon buns, Danish and donuts. Freshly baked rolls are piled up on tables for sale. Cellophaned cookie trays dot the store with sprays of color.

A customer walks in behind me. “It smells wonderful in here,” she says. I take a deep breath, though the wonderful smells are not new to me. For 21 years I’ve been walking into Eiselen’s Pastry Shoppe in Roxborough; long ago I became immune to its sweet smell.

It is the price I pay as the baker’s daughter.

I squeeze my way past the customers, give a nod to my sister, Allie, who is taking an order, and make my way to the back of the bakery.

Mom is decorating a cake. Dad is adding ingredients into the Hobart mixer. They both look up.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” says Mom. Dad just smiles as I put on my red apron.

There is an unspoken understanding that this Thanksgiving at our family bakery could be the last.

My father’s salt-and-pepper hair is lightly dusted with flour. Reading glasses, smudged with butter cream, hang around his neck. His “white” apron is a Rick Eiselen original – it’s spotted with evidence that he’s already been working for several hours: a brownie’s dark fudge, blue icing from a Happy Birthday cake, and the molasses of pecan pie.

I turn toward the store, ready to man my usual post as manager.

“We could use you back here, Dana,” says Dad.

He limps towards me, his body gently tilts to the right as he rests his hand on bench to bench for support.

In the unforgiving fluorescent lighting, he looks all of his 67 years.

Eiselen’s Pastry Shoppe is a full-line retail and wholesale bakery, making over 300 different products from scratch. My father takes pride in being able to make “whatever the customer wants.”

“In Northwest Philly, we’re the only bakery left like this,” he says. “There are niche bakeries that sell just cupcakes or just specialty cakes, but we put it altogether.”

We are known for custom cakes. My father was one of the original celebrity super bakers, he says. Cakes from Eiselen’s have been made for Philadelphia icons from The Phillies to the Mike Douglas Show and for landmarks such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art. They’ve been featured in movies, TV commercials, and at Tom Cruise’s birthday.

For 50 years, Eiselen’s has sat tucked away in the Ivy Ridge Shopping Center on the corner of Ridge Avenue and Domino Lane in Philadelphia’s Roxborough section, though this location is relatively new compared to the business’ colorful 114-year history in America.

Back to Germany

The Eiselen line of bakers extends back to the early 1800s in Germany. My great- grandparents emigrated from Germany in 1886 and opened two bakeries in South Philadelphia. My grandfather and then father continued the baking tradition. Our roots run deep.

Eiselen’s Pastry Shoppe went on to be Philadelphia’s first supermarket bakery for The Baltimore Market on Broad and Cheltenham, and later opened locations in Oak Lane, Erdenheim, Devon and lastly, Roxborough.

“In fourth grade, the teacher asked me what I wanted to do. I said I wanted to be a baker like my dad. Little did I know I’d still be in it,” he laughs.

A store girl interrupts. “Rick, do we have any more mince meat pies?”

He shakes his head: “No, this year they had to be ordered.”

It is a reminder that Roxborough is changing.

Mince meat pies are a flavor of generations past, and demand for individual desserts has put a dent in the market for large cakes.

My father has his theories. “Families aren’t as well-knit. Maybe both parents are working.” He pauses. “But there’s something to be said about everyone eating from the same cake.”

He covers his work bench with flour, takes a pan off a nearby baking rack, and flips it over onto the bench, releasing a 12-pound piece of Danish dough, one-sixteenth of the batch he mixed earlier.

“Help make the Danish.” says Dad.

I jump on this unusual opportunity to work in the back.For the first time, we are one Eiselen down at the shop. My younger brother, Ricky, did not come home from college for the holiday and the “Ricks” usually bake together.

I jump on this unusual opportunity to work in the back.For the first time, we are one Eiselen down at the shop. My younger brother, Ricky, did not come home from college for the holiday and the “Ricks” usually bake together.

Rick Sr. presses his large, calloused hands into the dough and tosses some flour on top, covering the imprints of his knuckles.

“Hand me a rolling pin.” The walk is exhausting for him.

Hip surgery to come

Sometime this month, he is due to undergo double-hip replacement surgery. For the first time in 50 years my father will take more than three days off work.

With the pin, he takes long, firm strokes, first top to bottom, then left to right. The evenly rolled piece of dough covers the 3-foot by 10-foot bench. He puts a pound of margarine in the middle of the piece and folds the two sides of the dough into the middle. Then he rolls the dough out again.

“We are developing the dough. We’ll put this piece away and come back to it in about an hour,” he instructs. The rolling and folding process is repeated three times to give the pastry a flaky texture.

He goes to another bench to inspect another baker working on the pie crusts. Then, he reads off a recipe for gingerbread from memory to another baker.

When he’s not looking, I grab the rolling pin.

My arms are weaker than I realized. I barely make an impression in transforming the next piece from loaf to sheet before he makes his way back to make it right.

Johnny Mathis’ rendition of “It’s Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas” plays on the store radio, but goes undetected as a wave of customers comes during lunch hour.

We duck our heads as bakers carry hot pans of pastry from oven to store.

I started helping in the store when I was just barely tall enough to see over the counters. Now, at 21, I am the most experienced person working.

“Dana, come back here,” calls Dad. The dough is ready to be filled.

I wash my hands while Dad prepares the bench. He scrapes off remnants of gingerbread dough which was just cut into hundreds of “men” and “women”.

The conductor

At the bakery, my father is like the conductor of an orchestra. He can play every instrument and knows the cadence of each composition.

His eyes scan the area as he rolls out the dough:

A fellow baker is at the bench across from ours, slicing bananas on top of the now custard-filled pie shells for banana cream pies. At a third bench, a baker is making jelly rolls.

My sister’s boyfriend, Ken, is learning how to flip donuts at the fryer. Another baker is watching the oven.

Allie comes in the back. “Dad, I got to run to class, but Mr. Steele was in the store and wanted to say hello,” says my older sister of two years.

My father smiles. “See Dana, everyone knows your Dad.”

Dozens of people today will ask “to see Rick.” Not only does everyone know my father, but he knows them.

Dad made Mr. Steeles’s wedding cake 40 years ago, and made every one of his kids’ birthday cakes growing up. Next month, the oldest daughter is getting married, and she wanted the cake from Eiselen’s.

My sister takes off her apron and shoots me an empathetic look. She is leaving us in the trenches mid-battle.

She is in her second year at Rutgers Law School. She knew for years that she wanted to be a lawyer, so after graduating from Bryn Mawr College in 2009, off to law school she went.

My sister is the first person in the Eiselen family to graduate from college, and also the first to pursue a career outside of the baking business.

I am a senior at Haverford College, majoring in economics, but am not sure what I want to do next. My younger brother is a freshman at Williams College, thinking of majoring in astrophysics.

My father takes a large, soft-bristled brush and paints a thin coating of egg wash over the dough. He dips his hand into a bucket of cinnamon sugar and spreads it over the egg wash.

The piece is folded in half, sandwiching the cinnamon-egg filling, and is rolled out again. The process is repeated once for each of seven pieces. Each piece will make 28-dozen large Danish.

It is my father’s belief that each bakery acquires a “one of a kind” taste, fixed and firm in the minds of its customers. “People came in when they were kids and, no matter where they go, they come back.”

Customer remembers our butter cake and crème donuts all their lives, and judge all else by the taste they grew up with.

“They say they can’t get anything like that anywhere else,” and come back for the taste of “good memories and a taste of home,” he says.

“A lot of people will be sad when the bakery disappears, but that’s what’s going to happen, Dana. It’s only me.”

Folding the Danish

It is time to fold the Danish. I’ve folded Danish before, but not since Christmas. Ken is going to learn, too.

The cinnamon-sugar filled dough is rolled out one last time. Quickly and precisely, my father makes three horizontal cuts and dozens of vertical cuts. He weighs each strip on a balance scale as four ounces.

Ken asks earnestly, “So are you taking over the bakery, Dana?” My stomach turns.

“Nobody’s taking over,” interjects Dad. “Nobody wants to.”

The tutorial continues somberly.

“Just like when playing a musical instrument, when baking, both hands work with the brain. That’s a sign of a good baker,” he says.

With two hands, he roles a strip on the bench into a snake-like piece. “Wind it up like a rubber band, but it has to be a gentle motion. See the ripple.” He smiles.

“Then will you sell it Mr. Eiselen?” asks Ken.

“I don’t think in today’s world, someone with no experience would last long in here.”

“You can’t just be a trained pastry chef and have a successful retail store, Ken. You have to be a jack of all trades. I try to be a jack of all trades and a master of none”

Over the years, people have shown interest in buying the bakery, and my father has turned down a few offers. “I’ve been holding on [to the bakery] so long my fingers are bloody,” he says.

His voice tightens. “It’s like riding down a cliff. You keep sliding but you don’t want to let go.”

He grabs an end of the snake-like strip, wrapping the dough into a spiral. The outer end of the snake gets tucked under the round piece and then is put onto a pan.

“In 60 years, there’s never been a day when I’ve been bored.”

Dad sits on a nearby stool. We have watched him work all day. Now, he watches us.

Ken and I start “winding” the pieces.

“Truth is Dana, I wanted you kids to have an easier life than I had, and that’s why I never pushed [the bakery],” he sighs.

He was never a scholar. He was an artist – and thought school would set his children free.

“I didn’t realize how hard you have to work in school to get anywhere,” he says. “Now I think maybe the bakery isn’t that hard after all.”

Ken and I are getting the hang of making Danish. Before finishing a pan, I tap each Danish with the egg wash brush.

“The bakery has served our family well. You’ve seen what hard work is. I think that’s what’s made you so good…But as I get older, I realized you have to work hard at any job to get somewhere.”

In a changing job market, he feels the bakery is a more appealing option for his children than it once was. “In most fields, when you get older, it’s harder to compete. But the longer you’re a baker, the better you get.”

He looks at his hands.

“It’s taken years to acquire the way something feels in my hands,” he says. “I can just taste what is should taste like. You can’t teach that, it’s an art. It’s job security.”

Pans of large Danish fill the rack, ready to be baked. My father leans over a nearby bench and props his body onto his side, struggling to get off the stool. He could ask another baker to roll the rack to the oven, but he doesn’t. He wants to do it himself.

“There is a satisfaction creating with your hands,” he says. “You’re starting from scratch, with a raw product, and taking it all the way through to a finished product. You’re creating a masterpiece.”

One by one, he pulls the pans off the rack and places them into the oven.

“You have to have it in your heart. If it’s not in your heart to be a baker, you can never be a baker. If it’s in your heart, it’s in your hands.”