How life at Bryn Mawr can stress students to the point of breaking

By Courtney Pinkerton

“If someone had described to me how my college experience would turn out three or four years ago, I would have stared at them in disbelief before laughing politely.”

But this 5’7”, lanky, brunette from New York City, in the midst of finals once again, is a different person than she was three or four years ago because of this experience, and even now wonders if it was for the best.

Before coming to Bryn Mawr College, Anne described herself as having been a well-adjusted, Honor student in high school. (We are using a pseudonym in exchange for her candor about her personal experiences.)

“I was high-achieving, just like my siblings,” she says, shrugging casually. “It’s a little bit of nature and nurture: we’re all pretty smart, but the environment we grew up, in between my parents and each other, also contributed to a culture of working hard in school and always trying to move ‘up’ in that regard.”

“I worked hard at a good school, but I wasn’t overwhelmed,” she continued, describing other “normalizing” aspects of her first eighteen years growing up. “I ran track, went to football games, had movie nights with the girls, and went on dates with guys.”

“It was a generally healthy lifestyle,” she laughs, “Complete with lots of friends and an appropriate sleep cycle!”

So, what changed after high school? After all, Anne went onto college that September just like her fellow high school graduates, and thousands of other 17- and 18-year-olds across the nation.

Yet, Anne didn’t go on to a school that automatically accepted her because she had graduated in the top 10 percent. Her college decision wasn’t determined by the institution’s vicinity to her childhood home, or because a family member was a graduate.

Anne chose Bryn Mawr College because “it’s a school with a great reputation for having a rigorous curriculum, a wonderful history, and a beautiful campus, and I fell in love with all of those when I researched the school online and visited the campus over Spring Break during junior year” of high school.

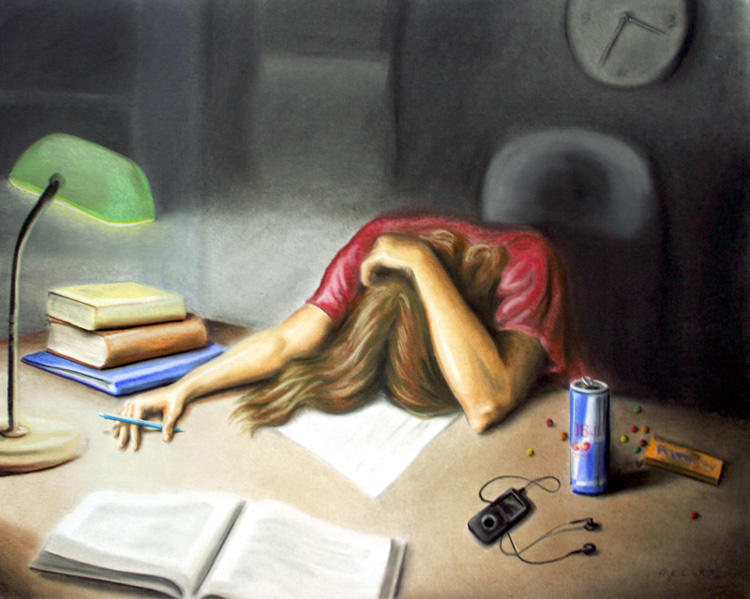

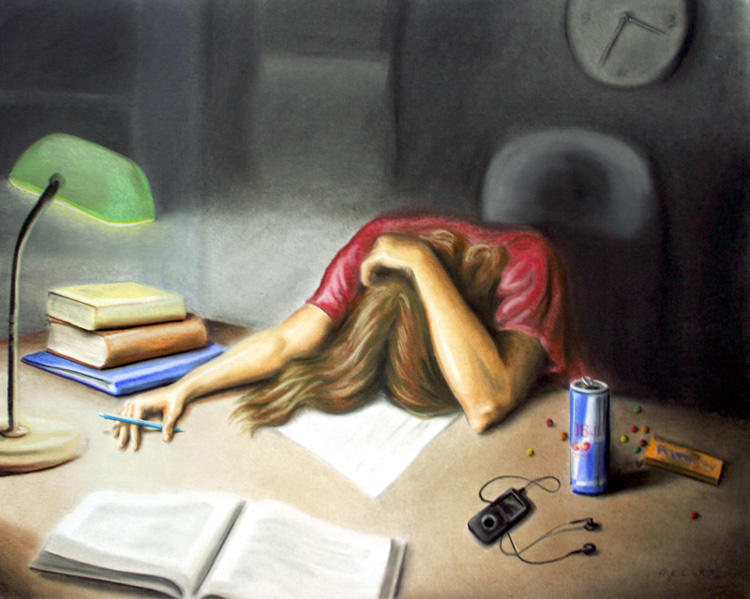

Indeed, Bryn Mawr is ranked the twenty-fifth top liberal arts college nationwide by U.S. News and World Report, but it is also listed among the25 institutions with the most rigorous workload, noted as “the schools that are most likely to keep you studying late into the night.”

In fact, it’s ranked higher for being a “demanding” school than a good one.

This report’s description is in line with what’s been reported about Bryn Mawr and other schools on the list lately: each of these top-tier campuses have become their own little microcosmic “stress cities”, possessing schedules and stress levels reminiscent of the lifestyle of a high-powered, corporate world member, or a new lawyer working in the criminal justice field.

“I didn’t expect to be stressed out for the sake of being stressed out,” Anne asserts. “Instead, I feel as though there’s a culture of stress here, and pressure to maintain it.”

“I don’t know who is feeling validated by such an environment, but it’s not healthy, appropriate, or worth bragging about,” she added. “And I’d like to be allowed to relax from time to time; I don’t want to feel guilty for getting a decent amount of sleep.

In fact, over the last few years, reports of overwhelming stress levels, associated behaviors, and other stress-related incidents have increased among students at the Bryn Mawr, according to student health and school public safety officials. It is especially visible during exam periods. Continue reading →