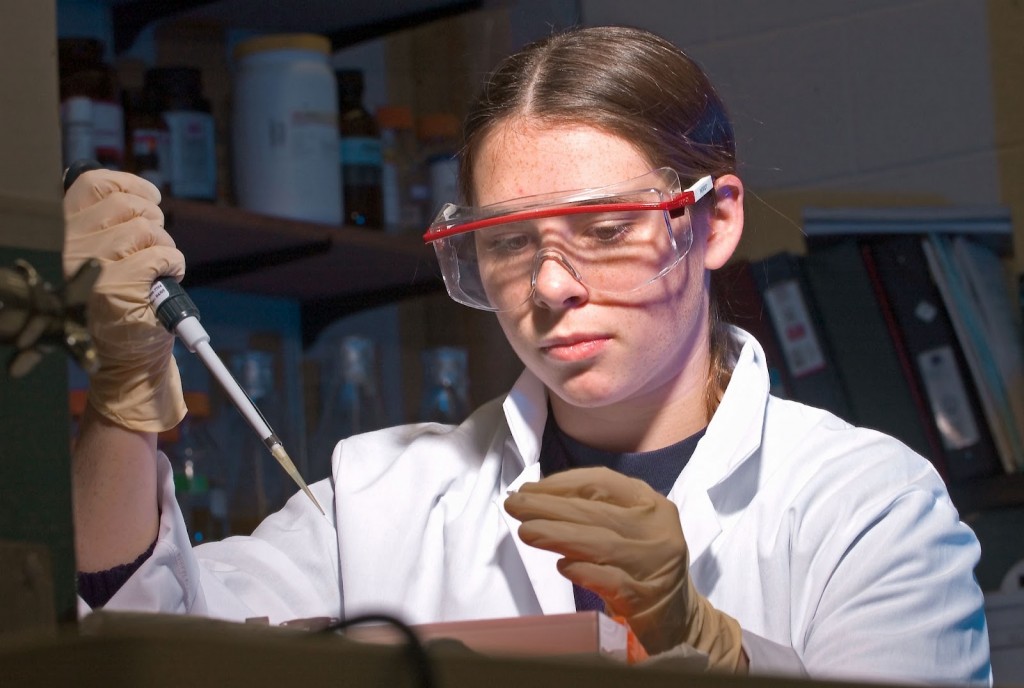

Why aren’t more women going into science & technology fields?

By Sydney Espinoza

The nonsensical hallways of the Park Science building at Bryn Mawr College are a combined source of frustration and humor among students. So much so that “I got lost” is a legitimate excuse for tardiness when getting to class involves navigating the building.

The women who decide to pursue majors in science, technology, and mathematics at Bryn Mawr are jokingly referred to as poor, lost souls who still haven’t found their way out of Park yet.

The women who decide to pursue majors in science, technology, and mathematics at Bryn Mawr are jokingly referred to as poor, lost souls who still haven’t found their way out of Park yet.

The infamous Park labyrinth has been steadily claiming more victims within its academic walls since 2006. Increasing numbers of science and technology majors at Bryn Mawr College reflects the nationwide push for women to pursue majors and careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields that, historically, have been largely male-dominated. Collectively, they are known as STEM.

“I’ve talked to women scientists who are a generation or a generation-and-a-half older than me and they had a rough road,” said Dr. Tamara Davis, Associate Professor and Chair of the Biology department at Bryn Mawr College. “Like for my graduate advisor, it was just hard for people to trust her, to give her credit that she was due. It was a lot harder for women in science thirty years ago.”

According to Bryn Mawr College’s Office of Institutional Research, Planning, and Assessment, an impressive 29% of its 1,300 undergraduates are pursuing majors in STEM fields, compared to the national average of only eight percent.

While a growing female presence within the scientific community is a promising step toward equal representation, another more-troubling national trend has become increasingly evident at Bryn Mawr: a largely disproportionate distribution of students pursuing majors in Biology versus other STEM fields such as Physics, Chemistry, and Computer Science.

To STEM or not to STEM?

The number of Biology majors has undergone exponential growth, and recently tied with Political Science and Psychology for third largest department, with 26 graduating majors in 2012. Yet, Physics, Computer Science, and Chemistry have remained relatively stagnant in the number of completed majors.

According to the Physics department website, Bryn Mawr College has averaged nine Physics majors per year, making up approximately three percent of the graduating class, and nearly 50 times the national average. The Computer Science and Chemistry departments report similarly flat figures.

So, what gives?

Even at Bryn Mawr College, women interested in pursuing science generally shy away from STEM fields that require more computational skill.

“I don’t know if it’s because they come in, if there is something that prejudices them against those fields before they get here,” said Davis, “my guess is that it probably is.”

She also discussed the pre-med track as a natural draw to Biology, explaining that 30% of incoming Bryn Mawr students think they’re pre-med, but only eight-to-ten percent of the graduates continue on to medical school. These statistics, she said, show how awareness of careers in a STEM field can impact the growth of its female population.

“I think students, women in particular, are often less aware of what their career options are in other STEM fields,” said Davis. “In your life, you have been to a doctor’s appointment, so you can kind of see that as a career option, whereas it’s harder to think about careers in engineering or even in academics as really a career. That might be something that more physicists would end up doing or computer programing.”

Lack of self-confidence?

Saba Qadir, 2013, a Biology major and student major representative for the department, voiced similar sentiments.

“As a country, girls are still discouraged from improving their self-confidence in math,” said Qadir, “the disparity at BMC is probably because it’s really difficult to reject or change a belief about yourself and suddenly become a ‘math person’ if it has been existing for several years of your life.”

Those within the Biology department aren’t the only ones speculating on this concerning issue.

Caroline Bruce, 2016, an undeclared Physics major, was surprised and troubled by the underrepresentation within the STEMs at Bryn Mawr, given the program’s stellar quality and one-on-one learning experience.

“There is a lot of support and a lot of small student-teacher close classroom experience, and they try their very best to make sure that the women who are in these programs are getting the best education,” Bruce explained, “and with that kind of resource and opportunity, I am surprised that [Physics] isn’t a much bigger major.”

She discussed her negative experiences with science in middle school and high school that almost kept her away from pursuing physics or any kind of science at all.

“I thought that that was a fault of the subject instead of the teacher,” Bruce said. “There was this scary idea that science was strictly labs, and if I couldn’t enjoy a lab, then I couldn’t enjoy the class; so I was afraid that if I pursued a major in Physics, I wouldn’t get a good grade, then I wouldn’t enjoy it at all, and it would spiral.”

Even at Bryn Mawr College, a virtual hub of female empowerment, breaking into more math-heavy sciences proves to be difficult for women. So now the million-dollar question: what can be done to get women excited about these fields?

Looking back to her own personal experience as a woman and science student struggling with the dominant male presence, Davis suggests bringing in more women—as faculty, as visiting alumnae, and as examples of success—to serve as role models in these fields.

“It’s already hard being a woman in these STEM fields,” she said, “and without having that role model network and support network for young women who are entering those fields, it’s just harder for them to sustain their careers and reach those goals.”

As for the future of those choosing to stay lost in Park Science, wandering in search of Physics, Chemistry, and Computer Science?

In time, said Davis. “I think it will get better in these other, more underrepresented fields over time, but I think it’s going to take some time.”