THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CONFEDERATE FLAG AT BRYN MAWR

By Kelli Breeden

It was a run-of-the-mill September afternoon and two seniors were finishing decorating their dorm rooms at the Radnor Hall residence at BrynMawrCollege. They turned to the small hallway alcove that gave way to their singles. A short time later, they stepped away to reveal a three-by-five foot Confederate flag occupying the stretch of wall between their doors and masking tape labeled “Mason-Dixon Line” separating themselves from the rest of the hall.

These students said they intended to make a statement of hometown pride, both having been born and raised in the Deep South. This would go unquestioned in a Southern university, but at Bryn Mawr, women’s liberal arts school outside Philadelphia, it would turn out to be a grievous mistake.

This decision, over the next few weeks, would completely alter their place in the college and reveal schisms within a school that prides itself on being an inclusive and cohesive community. What started as the independent self-expression of two students became a platform for larger racial issues.

This decision, over the next few weeks, would completely alter their place in the college and reveal schisms within a school that prides itself on being an inclusive and cohesive community. What started as the independent self-expression of two students became a platform for larger racial issues.

Remarkably, this whirlwind of events occurred in the span of two weeks. Emotions ran hot and blood boiled, but just a month after the events, campus had returned to normal. The students involved declined requests for comments, after being publicly named by local and national news.

All the quotations were gathered from campus meetings and events where the two women spoke to the community at large and other students spoke about their thoughts surrounding the incident. When asked about it today, students shake their heads and say they don’t really understand how it all happened so quickly and intensely.

Day One: A Flag Unfurled

The flag was put up, the line was put down, and the two students continued their day as usual.

Decoration in dorms on Bryn Mawr’s campus is the norm. Each year, dorm leadership teams get together to decorate halls before the rest of the study body arrives. Competitions are held to see which students can decorate their room the best, the winner receiving prizes such as a Kindle or a high number in the room lottery for the following year.

This leads to eclectic styles: a winner from 2013 collected gnome figurines and potted plants, filling her room with the little guys and countless artistic papers from postcards to full sized posters. One student papered a wall with maps of Philadelphia.

Ironically, while there are dorm rules that govern such items as type of adhesive used to hold décor in place, there are no rules censoring the content of what is put up.

This is considered a great thing at Bryn Mawr: walking down the halls, one can see anything from naked women to marijuana posters to Marxist iconography. This idea of self-expression is important here, where culturally taboo topics, such as gender identity and sexually, are encouraged and openly discussed.

Day Two: Side Looks and Murmurs

A college campus loves its gossip. Whispers around the dorm began, many recalling a rumor from last spring that a Confederate flag would be seen in Radnor Hall. Many felt that this large flag was too ostentatious and inflammatory, and spoke with Radnor’s dorm leadership team about taking action.

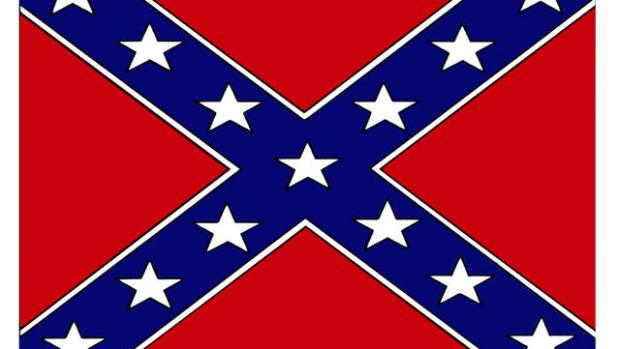

The issue that concerned most students was with the ties this flag has to racial issues throughout American history. The Confederate flag you see flown across the south today was in fact the battle flag of the troops lead by General Robert E. Lee as part of the army of the Confederate States of America in the Civil War. Americans remember this war in different ways: for some, it was a war over the continuation of slavery while others see it as a battle for states’ rights.

Regardless, the flag was re-appropriated in the 20th century in Alabama and Georgia to protest the desegregation of schools following Brown vs. Board of Education in 1956. From there it became a common symbol of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1950s and 60s.

What to do about the appearance of this flag? People turned to the dorm leadership team.

Dorm leadership teams, or DLTs, are comprised of several members, including dorm presidents, hall advisors, customs (orientation) leaders, peer mentors and community diversity assistants. These women are selected by their peers and trained to assist in conflicts that may arise through students from many different cultures, ethnic backgrounds, socio-economic classes, etc. living together. They are supported by graduate students of the School of Social Work and Social Research, as well as the Residential Life Office.

Day Three: The First Step

One of Radnor’s dorm presidents felt compelled to act after so many complaints from Radnor residents and growing awareness around the rest of campus. She held a private meeting with the two women, explaining the connotations associated with the flag and asked that they remove it. The students refused.

To them, the flag had “a stronger connection to home than the other messages” as one of the students explained in Q&A meetings following these events.

The discrepancy seen here was that while the ties to racial discrimination are apparent, so are seemingly benign associations of the flag with Southern heritage and culture. In WWII, regiments made of men mostly from the South used the flag as their unofficial banner. Today, it can be seen on t-shirts, flip flops, bumper stickers and more.

Day Four: “No Offense Meant”

While refusing to remove the flag, the women recognized the hurt fellow students were feeling. Thus, by midmorning, the flag in the hallway of Radnor featured an index card sign saying that it was a symbol of Southern pride and no racial insensitivity was meant by it.

Concerned members of the dorm leadership team sought a meeting with a member of the Residential Life Office “basically to find out what resources we had available to us in dealing with this issue” said a senior and Radnor resident. There weren’t any.

“We were told to handle this as best as we could,” the senior said.

However, at the same time, students of color approached representatives of the PensbyMulticulturalCenter to express their concerns over the public display of the flag.

This was another topic of debate. The two women were part of what is known at Bryn Mawr as a ‘hall group’ –a handful of rooms set aside for a group to select together so they can live with her friends.

These are often organized around the building’s unusual structures, which usually allow some separation of the group from the rest of the dorm. In this case, the girls did have a small inset of the hallway to themselves. They “thought it was a private space”, explained one of the students. However, it remained in clear view of the rest of the hallway, regardless of what section of wall it was on.

Day Five: Dorm Issue Goes Campus-wide

Another meeting was called between the dorm leadership team and the residents displaying the flag, officially asking that the flag be removed.

Recognizing the mounting opposition, the students agreed and moved the flag to one of their rooms.

If the DLT and two students thought this would resolve the issue, their hopes were dashed. While the flag was no longer in a public space, it was in plain view of the main campus green through the window.

What was considered a potential misunderstanding was now interpreted as a “blatant show of disrespect,” according to an anonymous student at a later Q&A session.

Other students throughout campus felt that the two women in question were purposely trying to create issues by first refusing to take down the flag, then by putting up a sign that could be construed as telling everyone to ignore their hurt feelings over the display of this symbol. Finally, when forced to take down the flag by dorm leadership, placing it in clear view of the not just their dorm but the entire school and any visitor walking through campus.

The two students later said they were “unaware of the impact” their actions would create. “I was not exposed to a lot of American history. I only knew what was around me, conversations [about the flag] were not being had in that light where I grew up and was not aware of how it effects people now” explained one of the students in a public forum. However, this ignorance was not considered enough by many students at the college, many calling for the women to be removed from Radnor Hall and not even be allowed to walk at graduation in May.

It was claimed that this is a violation of the Bryn Mawr Honor Code that states that one must have “continued commitment not only to our own environment, but to that of our sisters and brothers, result[ing] in the enrichment of our atmosphere, the strengthening of our foundation, and the constant reaffirmation of our community.”

This passage points towards an expectation for adherence to social responsibility – that when one’s ignorance leads her to harm others in her community, immediate and reconciliatory action ought to take place.

While these two students had so far done everything that had been officially asked of them, many doubted their sincerity and true beliefs.

Day Seven: Radnor Community Deliberates

A dorm-wide discussion with almost all Radnor residents took place; discussing reactions and what ought to be done about the situation.

No conclusion was reached. Outrage mounted amongst the students.

“The residents showed a blatant disregard for the feelings of fear and violation expressed by first years, students from the south, white students, and by students of color” said a group of 31 Radnor students in a letter to the public.

Day Eight: Bigger Than Two Students and A Flag

A meeting was arranged through the Bryn Mawr-Haverford-Swarthmore chapter of the NAACP to discuss and organize a demonstration in protest of the indifference the administration of Bryn Mawr to this issue.

While Bryn Mawr administrators considered it primarily a social issue and encouraged the dorm leadership to handle it themselves in an expression of self-governance, most students felt their reluctance to step in revealed a larger and systemic issue of failing to protect the rights and feelings of students of color.

Over 150 students and faculty attended the meeting, as well as key administrators, including Kim Cassidy, President of Bryn Mawr.

These women sought to “transform the campus-wide pain of a negative situation regarding the hanging of the Confederate flag into a positive, larger discussion about systemic race relation that our institution faces” wrote a member of the NAACP in response to this meeting.

Meanwhile, the blinds to the window revealing the flag were closed.

Day Nine: Protest and National Attention

That afternoon, several hundred students and faculty of all colors gathered together in solidarity for those suffering from the racial issues not addressed by Bryn Mawr’s administration.

Everyone wore black and linked arms to show their support. Signs declared sayings such as “Administrators silence speak volumes”, “Ignorance is not an excuse” and “Your privilege > my safety”. Hashtags such as #IfIWere, #BecauseIAm, #BMCBanter, and #RaceAtBMC were used in social media to support the demonstration and the call for change.

This demonstration brought outside attention. Local and national news outlets took note of the story.

Cassidy was supportive of the demonstration, saying in an email to the Bryn Mawr community that she “believe[s] our diversity is a strength and a mark of excellence and I am deeply committed to working together with you to create a campus climate that is experienced as safe and supportive by all community members.“

While she stated that both the issues experienced on campus and the rights of the two students involved needed to be considered, she was confident a reasonable decision could be made and Bryn Mawr could move forward through better diversity education.

This statement seemed to be saying that this was all a misunderstanding by the two students involved, and the school, while letting the student body resolve the issue, was deeply committed to the support and proper representation of the students of color at Bryn Mawr.

The flag was removed following the demonstration.

Gone but Not Forgotten

While the initial concern over the display of the Confederate flag had been rectified, many felt that the students in question were not forced to face the consequences of their actions. Many wanted these women to be examples for a stronger presence of a zero tolerance policy for racial bias and insensitivity.

In a signed letter, representatives of the Radnor community asked for the removal of the two women not just from Radnor Hall, but the campus residential community as a whole. “While we are unwilling to live in an environment with those students, we cannot, in good conscience, impose this threat on members of the greater Bryn Mawr community,” the letter said.

Bryn Mawr strongly supports the idea of self-governance. So, when a statement, such as the letter by Radnor residents, gives a clear issue and solution, and is backed by the majority of the residents at the residence hall, it is generally honored.

The two students were relocated to an off-campus apartment leased by the college.

Repercussions also found their way into the two students’ extracurricular lives.

As members of multiple athletic teams, their right to continue participation was called into question. Ultimately, it was decided that the students be allowed to keep their places on the roster. However, one of the students was removed from her leadership position as the secretary of SAAC, the Student Athletic Advisory Committee.

The events surrounding what began as a harmless, if misguided, display of hometown pride became a conduit for larger issues.

Two students raised in the South and ignorant of the racial implications of the Confederate Flag found themselves as symbols for the larger culture of passive oppression through a refusal by administrations to act quickly and decisively in instances of personal insensitivity and bias.

This led to their removal from campus, loss of leadership positions, and quasi-ostracism from the community at large.

Are these just consequences for the ignorant actions of two college students? Or are they an over-zealous response channeled by frustration at not being able to address racism on a larger systemic basis?