How the Posse Foundation helps students get into and thrive in college

By Nicole Gildea

Just relax. Yuying Guo tells herself as she steps into the interview room. Her stomach is full of nerves but she takes a deep breath and puts a smile on her face. This is not the time to be nervous. She has to give it everything. Her eyes scan the room and she notices about 24 other students. They all made it to the final interview but only 10 will be selected. Less than half of them. Guo hopes more than anything she will be selected because then she will win the ultimate prize—a full-tuition scholarship to college.

The interview lasts nearly four hours. It is a group interview where candidates answer questions about themselves and participate in interactive workshops. The selection committee already received her grades and test scores. Now they are evaluating her on her ability to communicate well, to work in a team, and to demonstrate leadership.

Guo leaves the building by the end of the night and steps into the December air. She feels a sense of relief knowing that she finished the third and final interview. She feels proud of herself for making it this far. Now all she has to do is wait for the decisions to be made.

Tiny flakes of snow flutter onto her jacket as she walks down the streets of Boston. She ducks into the subway and rides the train back home. She arrives home around 9:00 p.m. and settles into her bedroom. It is a school night. Homework will be due tomorrow. However, Guo is too distracted by the recent interview to do any homework.

Suddenly the phone rings. That’s weird. She thinks. Why is someone calling me this late? She answers the phone. A moment later a huge smile spreads across her face. It is the Posse Foundation on the other line. They are calling to tell her that she has been admitted into Bryn Mawr College on a full-ride.

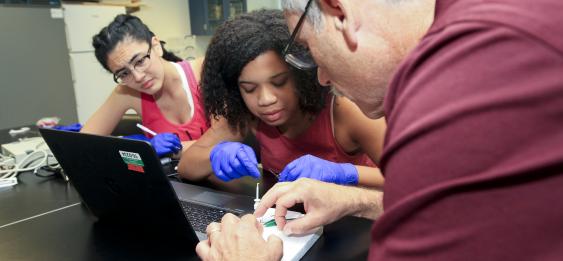

Posse students at in Bryn Mawr lab

Founded in 1989, the Posse Foundation is a national organization devoted to college access and youth development. Each year it identifies public high school students from the same urban communities who have demonstrated strong academic and leadership talent. The founder of the organization is Deborah Bial, an alumna of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. According to the organization’s website, Bial got the idea to create the foundation when she heard a student say, “I never would have dropped out of college if I had my posse with me.”

The Posse Foundation places students in diverse groups of 10, known as Posses, in prestigious colleges and universities throughout the United States. The idea is that by being in a Posse, students will receive the support of the fellow students their Posse to help them graduate. Continue reading