A library open for all of finals fosters a (stressed) community.

By Alison Robins

During finals week, students barricaded themselves on the site of the first Bryn Mawr College’s dean’s former home. For the next two weeks, the never-closed Canaday Library would be their office, dining hall, bathroom and bedroom.

Canaday, one of three libraries at Bryn Mawr, remains open continuously from the Monday of the last week of classes to the end of finals every winter semester. For some, the open-access to the study space and information trove is a blessing.

For others, it is a necessary curse.

“It’s a narrative of misery,” said Bridget Murray, a junior and a student worker for the circulation desk. “People don’t leave.”

In the wee hours of a Wednesday morning, Canaday was the great equalizer. The library could have been full of complete strangers, yet everyone had a similar story to tell: one of exhaustion and stress. Few escaped its hold—that is, until the morning light.

12:20 a.m.—“Wait, it’s 24-hour Canaday?”

The Lusty Cup café, located in the basement of the library, was abuzz with over 20 students as Tuesday turned to Wednesday.

All heads turned toward the door every time it opened to see who entered. Then, just as suddenly, the students would return to their homework, finals and Facebook.

“Wait, is 24-hour Canaday in session?” Asked Nehel Shahid, a sophomore. “Already? Sweet.”

Studying at Bryn Mawr circa 2011

Shahid’s confusion was understandable as the Lusty Cup, referred to as Lusty by students, was always open throughout the semester. The café aspect of the Lusty Cup—a student barista manning various coffee machines in a corner—was only open Sundays through Thursdays from 8 p.m. to midnight.

Shahid had just arrived, hoping not to pull an all-nighter. Last night, she stayed until 7 a.m.

“I’m more productive at night,” said Shahid. “It works for me.”

Her table, also occupied by two other students in this packed café, was covered in papers, computers and peanut M&M’s. One piece of candy flew from her hand to my face.

“Whoops, it’s that time of night,” she laughed.

Isabella Dorfman, a junior, was also unaware that 24-hour Canaday had started the night before. Her goal this semester? Not to watch the sun rise.

“That was awful,” she said, reflecting on her previous all-nighters. Yet, there she was, sitting at one of the available computers in Lusty.

“There’s a rhythm going in the room when it quiets down,” said Dorfman. She spoke about how the rhythm makes it easy to concentrate and get work done.

There are other benefits to the night owl environment: community.

“You don’t feel so alone,” she added. A beat. “That’s so sad-sounding.”

* * *

Walking through Canaday in the middle of the night was like being on a journey through a never-ending labyrinth. You must weave through stacks of decades-old books, dodge the odd carrel filled with tea and, sometimes, you locked eyes with another lost soul and felt a connection as if you two were the last people in existence.

Hidden in the back of the basement stacks, past Vietnam-era change machines, Bara’ Almomani, a senior, was passed out with her head on her laptop.

“I’m almost done…with my methods,” said Almomani, who perked up when she heard the approach of another human. She was working on her biology thesis, which was due the next day.

Behind her were whispering women seated at large tables. The table was covered in laptops, notebooks, papers, binders and drinks—in closed vessels, as is Canaday protocol. All their respective jewelry—bracelets, watches and rings—was off on the side. Nothing could interfere with their typing speed.

Committing to 24-hour Canaday meant avoiding all distractions: a difficult task, considering to leave even this floor, students must walk past tempting DVDs of distracting movies and television shows.

Placebo drunks

The library definitely had a different vibe during 24-hour Canaday, no matter the hour of day, according to its nocturnal student employees.

Kelsey Rall, a junior, worked at the circulation desk on the first floor. According to her, there were at least four times as many patrons in the library.

She would know: student workers must occasionally go through all five floors of the library to check for students and wake them up if they are unconscious.

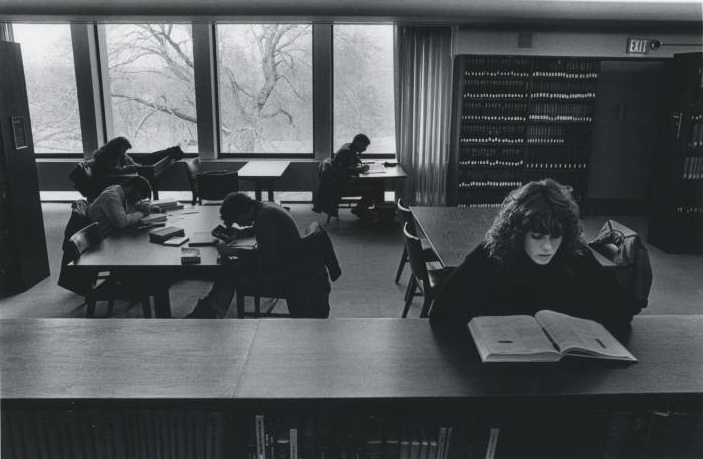

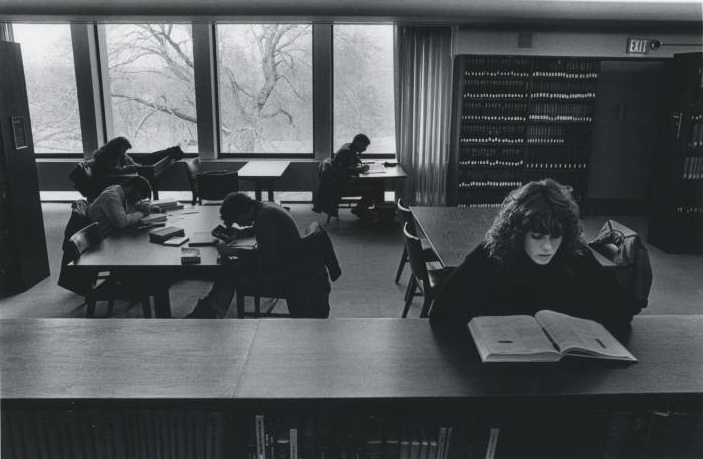

Studying in Canaday circa 1976

The difference between the Canaday of finals and the Canaday of the rest of the semester was not just its operating hours, but student attitude.

“People are acting more tired and more delirious than usual,” said Rall, no matter the time. When she was working, it was around 1 a.m., a time at which the library is normally still open. Typical weekday hours are 8 a.m. to 2 a.m.

Rall likened the student sentiment during 24-hour Canaday to that of when children are given grape juice but are told it is wine. They act drunk, though technically they are not.

Kelsey Peart, a senior and a Help Desk student technician, had a more positive outlook on 24-hour Canaday.

“I like it,” said Peart. “I am getting paid to do homework right now.” Though the first floor was packed with students, no one was coming up to her for tech advice.

As most of the Canaday employees were also students, Peart noted, “I’d be here otherwise,” in reference to the work she had to do this finals week.

Though the Special Collections department was closed and the reference librarians had gone home, the Help Desk, almost equally unneeded, remained open.

“No one needs their passwords changed, I guess,” said Peart.

* * *

Mimi Gordor, a junior, was leaving the library…for now. She was coming back.

“I am in my day clothes and I need to be more comfortable to be more effective in my studies,” said Gordor.

Gordor lived on campus, so she could in theory just study in her room. But rooms have beds, and that was no good for her.

“My friend wanted to study, and I feel more productive when I am in Canaday for some reason?” Gordor said, her voice rising on the last word. “Just not seeing my bed is good for my study life.”

Was tonight an all-nighter in the making? Gordor was not sure.

“I will stay until the work gets done,” she said. “It’s not about me, it’s about the work so…until I’m fully satisfied that I have at least 70% of what I came to do done, I’m not leaving.”

Gordor had a portfolio due at the University of Pennsylvania in 15 hours. She was just going to stay and work on it until they kicked her out of the library—she did not know 24-hour Canaday was in session.

“Yeah, I was just going to wing it,” she laughed.

“Quiet” floor

As students entered the third floor of the Canaday library, M. Carey Thomas haunted their very souls. That is, a bust of her face stared at student’s backs as they walked through the doors separating the stairs from the stacks.

One student sat in the stacks studying as the hours ticked on. She would not leave that spot the whole night.

Continue reading →

It would be natural to assume that grades, and their anticipation, play a large role in this stress and worry, even though both colleges they do not emphasize grades and discourage their students against discussing them too much. This is done in the name of creating a less stressful learning environment.

It would be natural to assume that grades, and their anticipation, play a large role in this stress and worry, even though both colleges they do not emphasize grades and discourage their students against discussing them too much. This is done in the name of creating a less stressful learning environment.