Bryn Mawr gets high marks from Chinese students….

But many wonder if the understands them.

By Yuqi Zha

The number of Chinese students at Bryn Mawr College has increased 20 times in 10 years, from only nine students enrolled in 2008 to 181 Chinese students enrolled in 2018, according to Patricia Lausch, the director of International Student and Scholar Services and Advising at Bryn Mawr College. Chinese students now represent 13% of the total student population, the largest single group of international students.

What do Chinese students think of Bryn Mawr College?

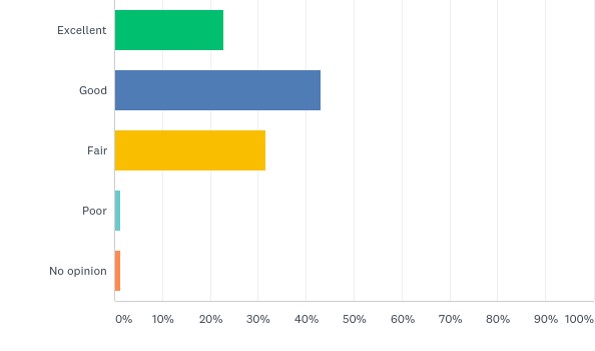

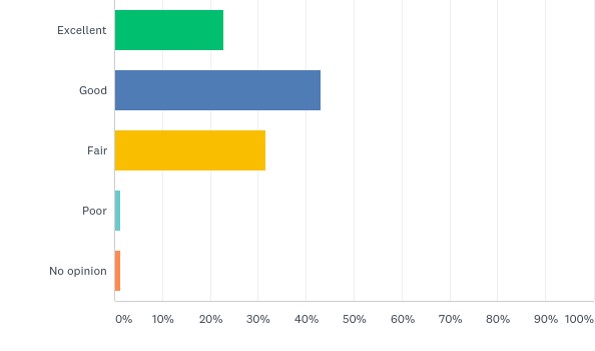

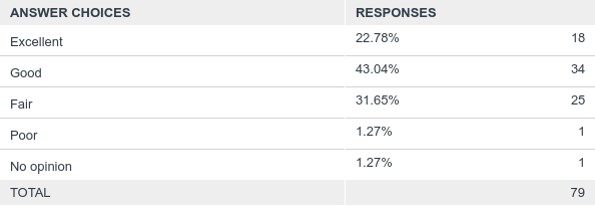

To find out the answers, we surveyed all of the Chinese students on campus, including a few recent graduates, and interviewed eight respondents. Seventy-nine students answered our survey, which is a 43% response rate, high for a voluntary survey. In addition, 31 students appended anonymous comments to the survey sent out through Survey Monkey in late April. Chinese students are willing and eager to share their feelings and opinions.

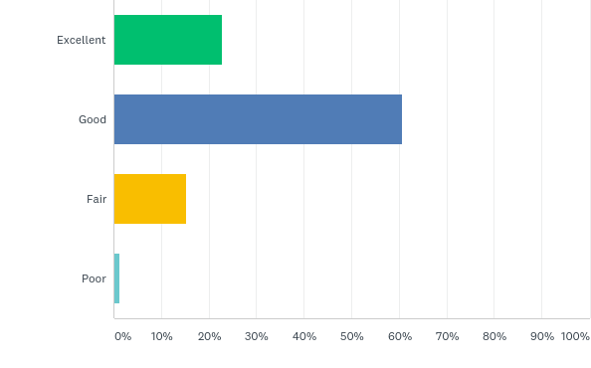

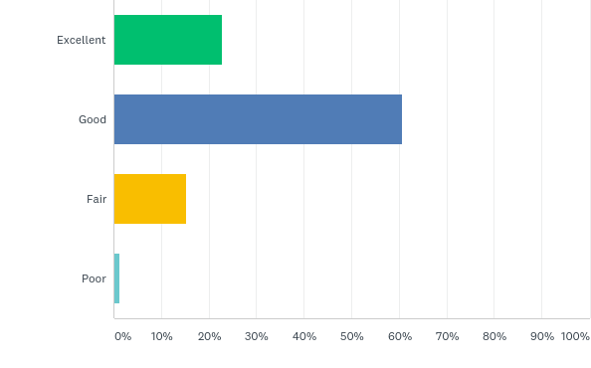

Overall, Chinese students are pleased with their experience at Bryn Mawr, with 24% rating it excellent and 61% rating it good.

Q: Overrall, how would you rate your experience at Bryn Mawr?

They also have a generally favorable opinion of the services they use. The percentage of students rating each service good or excellent are: 73% for the Pensby Center for international students, 65% for the Writing Center, 63% for the Health Center, 67% for the New Dorm Dining Hall and 59% for the Erdman Dining Hall. The one exception was the Counseling Center, considered good or excellent by only 35% of the respondents. The low rating of the Counseling Center is partly influenced by the fact that fewer Chinese students have contacted with the counseling service.

As one respondent to the survey put it: “Without BMC I would not be who I am. In my four years here, BMC not only taught me priceless professional knowledge and expanded the scope I interpreted the world around me, but also helped me have a better understanding of myself. I learned critical thinking here, but more importantly, I learned tolerance from the open and comprehensive environment of BMC.”

Praise was not universal. When asked if the school offered a welcoming environment, 33% students rated it fair or poor. Another 34% said they had experienced some discrimination at the school.

Interviews with students fleshed out some of those feelings. Some aspects of the college have not adapted to the explosion of Chinese students.

In sum, Chinese students want improvement in three areas: They want staff with Asian backgrounds on the campus. They want International Student Orientation back. They want attention to their particular needs and not be the “invisible yellow” anymore, as one student put.

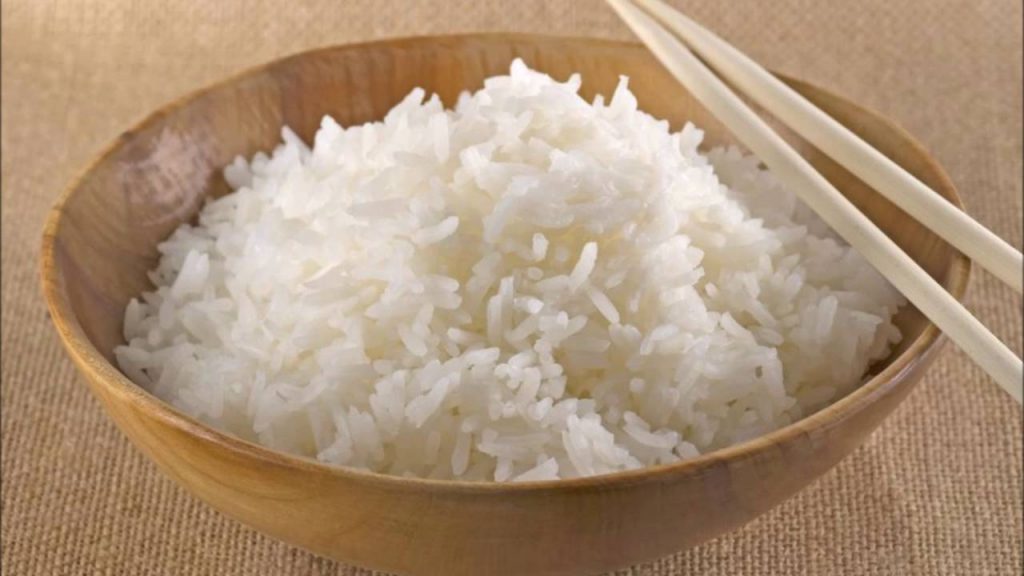

There is one issue that symbolizes that failure to adapt. It centers on the issue of white rice.

Bryn Maw College offers Chinese students lousy white rice.

White Rice

White Rice

Bryn Mawr College has two dining halls, the New Dorm Dining Hall and the Erdman Dining Hall. Erdman provides only traditional American food, while the New Dorm has a special buffet, devoted to food from different countries and regions around the world, including Chinese and other Asian food. Students call that part of the New Dorm Dining Hall the special bar. The origin of the food provided on the special bar changes every month.

Probably because of the special bar, Chinese students slightly prefer the New Dorm Dining Hall over the Erdman Dining Hall: 87% said they frequently use the New Dorm Dining Hall, compared to 67% who said they frequently use Erdman Dining Hall.

When the special bar in the New Dorm Dining Hall provides Asian food, it also provides white rice, because white rice is the basis of Asian food. Asians have very different opinions about rice from Americans. They like tender, moist, sticky and fluffy white rice, very different from brown rice. If cooked white rice has the same hard and chewy taste as brown rice, it is considered as “half-cooked” and terrible by the Asians.

The white rice provided at the special bar followed the American standard of preparation. That’s why Chinese students had many complaints about it.

“I don’t really understand how they can make white rice taste so bad,” said Cheyenne Zhang, a sophomore Math and Philosophy major.

“Is it so hard to cook white rice? Come on, it’s just white rice!” said Hou Wang, a senior Fine Arts major.

“It’s true that Chinese food has many regional cuisines and it’s hard to satisfy all the Chinese students from different parts of China, so I don’t even want to comment on the Chinese dishes on the special bar. But I just want a bowl of normal white rice every day,” said an anonymous respondent to the survey.

Probably, there is no other culture that can exceed the extent to which Chinese culture values food.

“Food is the first necessity for man,” according to an old Chinese saying.

Therefore, if a bowl of white rice can make the campus a much more comfortable environment for Chinese students, why not make the change?

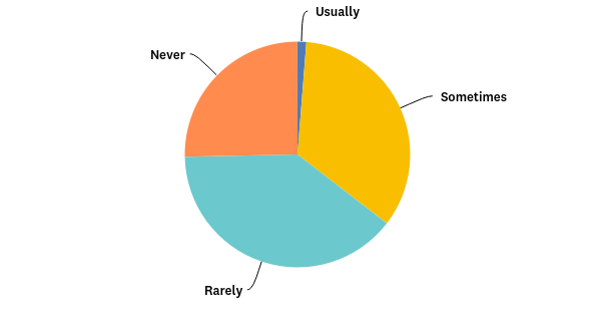

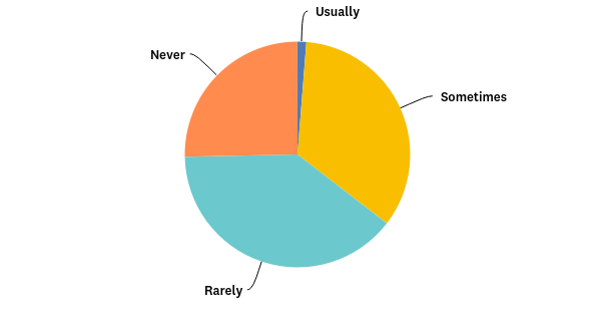

Q: Have you ever felt discriminated against at school because of your nationality?

Staffs with Asian Backgrounds

Shining Zhu, a junior Psychology major, who has worked at the New Dorm Dining Hall for three years, provided an answer—lack of student supervisors and managers with Asian backgrounds at the New Dorm Dining Hall.

“They think sticky and fluffy white rice is gross,” said Shining Zhu, referring to American staff and student workers at the New Dorm Dining Hall.

The student supervisors and managers at the New Dorm Dining Hall are predominantly white, so the food provided there is according to an American standard, including the special bar.

“There isn’t anyone to represent the opinion of Chinese student workers or Chinese students in general at the weekly staff meeting,” said Zhu, “Chinese students might be afraid or nervous to give advice directly to the managers or the college.”

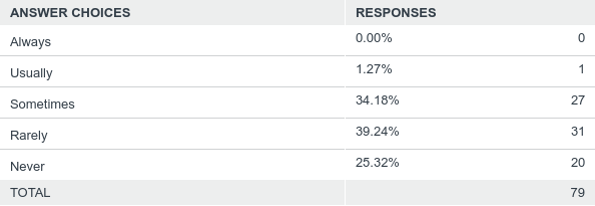

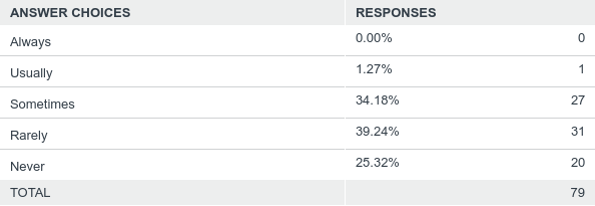

The New Dorm Dining Hall is not the only place lacking staff with Asian backgrounds. Out of the six services surveyed, the Counseling Center was the least frequently used by Chinese students, with 71% saying they rarely or never used it.

There are complicated cultural and social reasons behind this phenomenon. In China, the education system doesn’t pay much attention to the mental health of students. Therefore, many Chinese students didn’t realize that the Counseling Center was an option they could go to when they encountered problems.

Four out of eight interviewees mentioned that they didn’t think they needed any counseling service, but they also mentioned that they felt homesick or stressed, especially in their freshman year.

Another important reason behind the low usage of the Counseling Center is the language barrier.

“I am afraid that I can’t express myself clearly in English, especially for emotions and feelings,” said Jia Wei, a freshman, “The multilingual service of the Counseling Center is only available in Spanish. Therefore, I didn’t use it frequently.”

“It makes me sadder when I need to pour out my fears and worries in English,” said one respondent in the survey.

The presence of an Asian psychiatrist or counselor may encourage Chinese students to use the Counseling Center more often.

The phrase “a dean or Admin staff with an Asian background” also appeared frequently in the comments from the survey.

“I think the only way to ensure that Bryn Mawr creates a supportive environment for international students (Chinese students particularly in this case) is to hire an official dean with a real Chinese background—not someone who grew up abroad but someone who really knows the academic, cultural and professional barriers that Chinese students face,” said one survey respondent.

“We don’t even need an Asian dean, but just someone who really understands Asian culture,” said Hou Wang, “someone who can really understand us.”

All the interviewees agreed that this would be a good idea.

“It’s not like we want an Asian dean to handle all the Asian students, but the mere presence of such a dean will help us feel safer and have more sense of acceptance,” said Wang, “the psychological effect of such a dean or admin staff is very essential. We will feel recognized by the college.”

As in the case of the New Dorm Dining Hall, Chinese students want a dean or a member of the administrative staff with an Asian background to function as the connection between them and the college.

“I feel like if we have such a dean, the dean’s office and the administration can consider the need of Chinese students better when they organize activities or make decisions,” said Siyuan Luo, an alumna who graduated in 2017.

“Invisible Yellow”

Fifty-six percent of Chinese students said they never or rarely encountered discrimination on campus. However, 36% percent of Chinese students said they felt discriminated against usually or sometimes because of their nationality Surprisingly, most of these experiences were academically related. It is hard for many professors and domestic students to recognize or respect the struggle international students face, especially when it comes to language.

Luo described her experience in a class called Introduction to Modern Architecture: “I got a really bad grade on my first paper and I decided to talk to the professor. The first thing she said in our conference is ‘I can’t understand your English. I think you should withdraw from this class’, without telling me what I did wrong or helping me improve. I am an East Asian Languages and Cultures major and I have to do a lot of writing. But I never got the similar comment from any other professors.”

In the end, Luo withdraw from the class because she was afraid that the professor wouldn’t offer her any help to pass the course.

Gaoan Sheng, a freshman, encountered great difficulties when she tried to communicate with her classmate in ESEM. ESEM is a seminar course all the freshmen have to take, in order to prepare them for academic writing and discussion.

“The American student sat next to me every class,” said Sheng, “but whenever the professor asked us to discuss in pairs, she always ignored me, even if there was no one else she could discuss with.”

Sheng felt especially hurt when she saw that student happily talking with other students both in class and after class.

The discrimination that Chinese students encountered was mostly due to certain stereotypes about Chinese in American culture, ignorance about Chinese culture and a lack of understanding of the recent development of China.

“It’s not really about feeling discriminated, but about feeling ignored,” said Wang, “We are part of the ‘invisible yellow’ in the American society.”

Chinese students themselves have to take some responsibilities for this invisibility. Compared to other ethnic groups on campus, Chinese students are quieter when it comes to campus-wide conversations on many issues.

As one respondent to the survey said, “I wish Chinese students could engage in more panel discussions on campus, or hold the panel discussions themselves.”

Part of this reticence is due to Chinese culture—Chinese are used to tolerate and adapt themselves to difficult conditions. They are good at changing themselves to fit into the environment, but not at changing the environment for themselves.

However, another essential reason behind the “invisibility” is the feeling of insecurity Chinese students face on this foreign land.

“Because we are living on a foreign land, sometimes I felt I don’t have the right to comment on things,” said Eva Liu, a sophomore Biology major, “I am afraid that I will be attacked if I ask them to change. In the end, they are the owners of this land, you know.”

“I am sorry that sometimes I am a coward,” said Wang, “When I heard people having silly conversations about China, I didn’t have the courage to correct them. Because this is not our home, we can’t always say what we want.”

Chinese students also don’t have a student association that can organize and represent their voices in the campus-wide conversations. Probably this is something Chinese students have to work out themselves. But if the college can appoint a dean or admin staff with an Asian background, they may alleviate the feeling of insecurity of Chinese students and give them more courage to speak out on this foreign land.

As the number of Chinese students increases, more and more Chinese students do speak out or participate actively in campus-wide activities and discussions.

“I am really grateful for those who actively raise their voices on campus, like Koukou Zhang in the LGBTQ movements and Xiaoya Yue in SGA,” said Wang, “but for some reason, their efforts as Chinese students ended up invisible. I don’t know why and I don’t know how we could change.”

Q: Rate the efforts made at the school to create a welcoming environment for Chinese students.

International Student Orientation

International Student Orientation

Surprisingly, Bryn Mawr College recently made a change regarding international students, but a negative one. Bryn Mawr College will no longer have International Student Orientation (ISO) for freshmen, starting from next fall.

Originally, international students would come to campus two days earlier than domestic students for the ISO. The college would take the students to get their Social Security numbers and arrange a series of events to help the students adapt themselves to this new environment. International upperclassmen would work as volunteers during the ISO to take care of the freshmen.

In the interviews, when asked about the best thing the college has done for international students, half of the interviewees mentioned ISO.

“ISO provides a soft landing for international students,” said Eva Liu, “we were able to meet students from the same origin first before we were fully exposed to this unfamiliar environment.”

“International students need more time to adapt themselves to this new environment,” said Cheyenne Zhang, “even just for the jet lag.”

“It’s a perfect chance for upperclassmen to know freshmen,” said Gaoan Sheng, “it’s crucial for freshmen to have this bond with upperclassmen from the same origin. Because they are the only people on campus who can understand the struggle that the freshmen will go through.”

However, the freshmen coming in 2018 will no longer have all these experiences.

At the end of a long welcome back email from Patricia Lausch to all the international students during this winter vacation, she said, “International Student Orientation will be incorporated into Customs 2018. If you are interested in greeting incoming students, consider applying for a Customs positions.”

Customs is the general orientation for all freshmen at Bryn Mawr College.

“I knew ISO was canceled only when I decided to apply for ISO assistant and contacted Patti,” said Sheng.

The situation was the same for Jia Wei.

“I think they should at least give us an explanation,” said Wei, “Patti mentioned in a meeting, not about ISO, but something like ISO was canceled because the number of international students has increased and we can take care of ourselves. I don’t understand the logic at all.”

“I feel bad for the freshmen coming next fall,” said Liu, “they will see all the parents of the domestic students helping them moving in, while they are alone in this strange land. And they will only have Customs People to help them, who wouldn’t be able to offer any help.”

The Customs People are student volunteers working during the Customs and throughout the whole year. They help organize traditional events to welcome the freshmen to the campus. Each floor of each dorm will have two Customs People. However, during the interviews, freshmen and sophomores had many complaints about Customs People.

“My Customs People never showed up in any events,” said Wei, “she didn’t even greet me when we encountered in the hallway.”

“Many Customs People don’t care about their responsibilities at all,” said Sheng, “they just care about the good single room they can get.”

In exchange for their work during the year, Customs People get the opportunity to choose one of the best single rooms on each floor. Room Draw at Bryn Mawr College is a random process—each student will get a number randomly and choose a room based on the sequence of their assigned numbers. Only the first 100 students of each class year can get a good single room. Therefore, applying for the Customs people becomes a good way for many students to avoid the risk of bad luck in the Room Draw.

“I don’t understand why and how the college made this decision about ISO,” said Sheng, “it’s definitely not because of lack of ISO assistants. Many freshmen like me are very passionate and willing to become ISO assistants.”

As the number of international students increases, the resources, especially money and staff, devoted to international students haven’t increased accordingly. Therefore, the attention that each international student receives decreases.

“I don’t want to feel like an ATM, but sometimes I do,” said Wang, “we paid so many full tuitions to the college but they cared less and less about whether we feel good or not.”

Wandering between beds of produce–carrots sprouting in one bed, spinach in the next—Ellis Maxwell, my tour guide for the afternoon, identified plants as we walked. The spinach under the tarp here was recently planted and would grow quickly. The onions here would grow over the winter and could be harvested in early spring. These rows had already been harvested so the green ground cover was revitalizing the soil.

Wandering between beds of produce–carrots sprouting in one bed, spinach in the next—Ellis Maxwell, my tour guide for the afternoon, identified plants as we walked. The spinach under the tarp here was recently planted and would grow quickly. The onions here would grow over the winter and could be harvested in early spring. These rows had already been harvested so the green ground cover was revitalizing the soil.

White Rice

White Rice

International Student Orientation

International Student Orientation By Yi Gao

By Yi Gao

By Sean Woodruff

By Sean Woodruff