Bryn Mawr’s Ludington Library remains a vital part of the community

By Deeksha Raina

On a Wednesday afternoon in the Ludington Library in Bryn Mawr, there isn’t a single empty table in sight. Every table, including the ones tucked away in remote corners of the library, has at least one occupant, ranging from small children laughing over a picture book to college students furiously typing away on their laptops, head bobbing to whatever tune is blasting through their earphones.

In the airy indoor reading porch, an elderly couple sits together sipping on coffee and thumbing through their books. A few tables away, a high school student practices speaking in French with her tutor. Despite it being a weekday afternoon, the library is bustling and full of life.

The Ludington Library, one of the libraries of the Lower Merion Library System (LMLS), is just one of many that have managed to keep the library relevant to the community in the new digital age.

Roz Warren, a library assistant at the Bala Cynwyd Library, another library in the LMLS, noted, “In the old days, when there was no internet and you had to write a report or research paper, you would come into the library to find research material. But now that’s not really the case.”

Public libraries are no longer document-centric, shifting towards a user-centric model instead. It’s no longer about the books that libraries have. Rather it’s the range of services one central location can provide for its community.

Today, libraries provide so much more than just books and dvds. The Ludington Library, among others, provides community members with meeting rooms, access to computers, wifi, tax forms, and even baking pans shaped like teddy bears and trains. And of course, the library provides students with a much-needed quiet environment to study.

The Ludington Library is not alone in these changes. In 2015, the American Library Association (ALA) president Sari Feldman said, “Today libraries are less about what we have than what we can do with and for our patrons.”

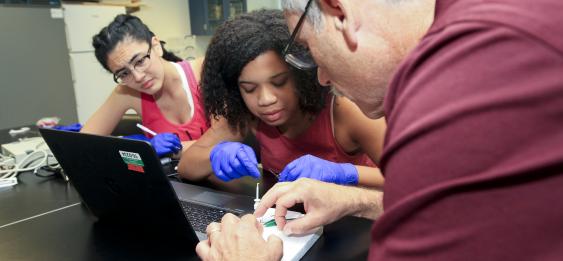

Public libraries have added computers, wifi, access to printing services, and digital literacy programs to the core of their services. Unsurprisingly, with such additions to the library, visitors continue to stream in and the data is there to back it up. In 2012, the American Library Association found that there was a 54.4% increase in visitors to public libraries over the past ten years.

Public libraries have added computers, wifi, access to printing services, and digital literacy programs to the core of their services. Unsurprisingly, with such additions to the library, visitors continue to stream in and the data is there to back it up. In 2012, the American Library Association found that there was a 54.4% increase in visitors to public libraries over the past ten years.

By Yuqi Zha

By Yuqi Zha